BepiColombo rediscovers Mercury’s electrons, 50 years after Mariner 10

A technological leap towards Mercury: BepiColombo reveals the dynamics of electrons in the magnetosphere of the planet closest to the Sun.

Mercury, the smallest planet in the solar system, is still a largely mysterious world. Its proximity to the Sun leads to complex interactions between its magnetic field, its very thin exosphere and the solar wind. These phenomena create an extremely small magnetosphere, so small that it could fit entirely inside the Earth’s, and for which the role and dynamics of electrons remain to be clarified. The BepiColombo mission, launched to shed light on these mysteries, comes at just the right time, 50 years after the last observations of these populations by Mariner 10 (1) .

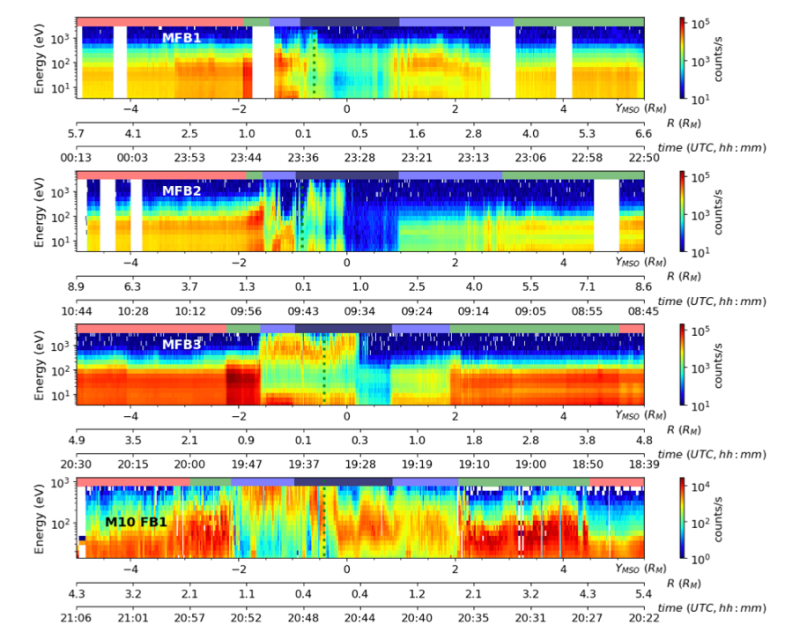

BepiColombo (2), on its way to Mercury where it will enter orbit at the end of 2025, is equipped with state-of-the-art plasma instrumentation. These instruments enable us to study the properties of charged particles in Mercury’s magnetosphere, in particular thermal and suprathermal electron populations. A team involving CNRS Terre & Univers researchers has analyzed the data collected during the first three Mercury flybys in October 2021, June 2022 and June 2023 by the MEA (3) electron analyzers onboard the Japanese Mio satellite.

Energy-distance spectrograms of electron count rates observed by MEA reveal the dynamics and variability of interactions between the solar wind and Mercury’s magnetosphere. On the first flyby, the magnetosphere was compressed; on the second flyby, it was close to its average state; and on the third flyby, it was again strongly compressed. The electron densities and temperatures measured by MEA vary between 10 and 30 cm-3 and above a few hundred eV (4) when entering the magnetosphere on the night side, and between 1 and 100 cm-3 and well below 100 eV before exiting the magnetosphere on the day side. These densities are 4 to 10 times higher than those recorded in 1974 by Mariner 10, thanks to MEA’s increased sensitivity and energy coverage.

These new data offer an unprecedented view of interactions in Mercury’s magnetosphere, and a better understanding of electron dynamics. They open up new perspectives for the study of similar planetary environments, laying the foundations for future research into magnetic and electrodynamic processes in our solar system and beyond.

Notes

- Mariner 10, launched by NASA in 1973, was the first space mission to carry out flybys of Mercury.

- BepiColombo is a joint mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to explore Mercury.

- MEA (Mercury Electron Analyzers) are instruments supplied by IRAP. Carried aboard the Japanese Mio satellite, they are used to measure electron populations in Mercury’s magnetosphere.

- Electronvolt, the unit of electron energy measurement commonly used in particle physics.

CNRS laboratories involved

- Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie (IRAP – OMP) – Tutelles : CNRS / Université Toulouse III Paul Sabatier / CNES

Further Resources

- Scientific Publication : Rojo, André, et al., Structure and dynamics of the Hermean magnetosphere revealed by electron observations from the Mercury electron analyzer after the first three Mercury flybys of BepiColombo, Astronomy & Astrophysics, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202449450

- CNRS Press Release : BepiColombo redécouvre les électrons de Mercure, 50 ans après Mariner 10

IRAP Contacts

- Nicolas ANDRE, IRAP et ISAE/SUPAERO, nicolas.andre@irap.omp.eu et nicolas.andre@isae-supaero.fr

- Mathias ROJO, IRAP, mathias.rojo@irap.omp.eu